After a long period on the fringes of the national conversation, the matter of President Trump’s mental health has taken center stage since the publication of Michael Wolff’s blockbuster book Fire and Fury. The book includes testimonials from former White House chief strategist Steve Bannon and others that paint a picture of the president as a semi-literate ball of rage with a nonexistent attention span who is cognitively declining before our eyes.

In response to the fallout, Trump called himself a “very stable genius” on Twitter and held an open meeting that seemed designed to prove his mental acuity, two moves that only drew more attention to the state of his addled brain.

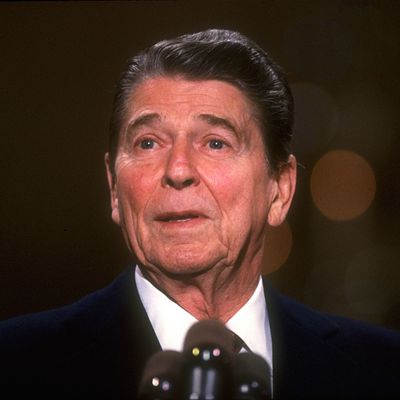

A lot about this administration is unprecedented — or as Trump might say, “unpresidented.” But in the case of a president’s fitness to serve, recent history may act as a very rough guide. To grapple with the idea that the man running the United States may not be in full possession of his faculties, one need only turn back the clock about 30 years to President Reagan’s second term.

In 1994, Reagan revealed in a letter that he was suffering from early-stage Alzheimer’s Disease. He died in 2004.

Whether Reagan was suffering clear symptoms from Alzheimer’s while in office has been a subject of fevered debate for many years. In 2011, his son Ron Reagan wrote in his book Reagan at 100 that he felt “something was amiss” with his father’s mind during his second term, though the younger Reagan later clarified that this did not mean that the president was suffering from dementia during that time. The book drew a fierce backlash from conservative Reagan defenders, including the former president’s other son, Michael, who insisted that his father was perfectly capable throughout his White House tenure — a conclusion that had previously been reached by Reagan’s four personal doctors and other memoirists who were close to him. (A sketchily sourced Bill O’Reilly book released in 2015 was renounced by the president’s inner circle.)

But multiple journalists have testified to a complicated reality: a slowly diminishing executive who leaned increasingly heavily on advisers, disengaged from day-to-day affairs, and sometimes had difficulty distinguishing fantasy from reality.

The way these accounts were handled at the time highlight the differences between the 1980s and our own turbulent era, and the differences between Reagan and Trump. Here’s a look back at how key segments of the political world handled Reagan’s mental state.

Democrats Pounced, Then Left the Issue Alone

As Ronald Reagan ascended the national stage in the late 1970s, the former Hollywood star and governor of California had already honed his reputation as the avuncular “cowboy,” a persona he would perfect in the White House. He was a man who thought in broad strokes, but was prone, even before he became president, to forgetting stories and details, tendencies his opponents attacked as proof that he was too old to lead. Reagan was no spring chicken, after all; at 69, he was the oldest person ever to be elected president when he won in 1980. (Trump, elected at 70, broke the mark in 2016.) Reagan addressed such concerns head-on. He vowed to resign the office if he was ever found mentally unfit by White House doctors.

Democrats most seriously exploited concerns about Reagan’s age four years later, when the president appeared confused at multiple points during his first debate with Walter Mondale in 1984.

“Reagan showed his age,” Tony Coelho, chair of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, said afterward. ”The age issue is in the campaign now and people like me can talk about it, even if Mondale can’t.”

Reagan appeared much sharper in the second debate, subduing his opponent with a famous, rehearsed quip: “I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent’s youth and inexperience.”

He won a landslide victory in the fall, and there was no concerted effort by Democrats to question his fitness again.

While it’s overdoing it to cast the 1980s as some sort of bipartisan paradise compared to our hyperpolarized era — again, there was plenty of discussion about Reagan’s fitness from 1980 onward — it is true that a different, more genteel set of political norms applied. There’s also the matter of public opinion. Unlike Trump, Reagan was more liked than disliked by Americans for a large chunk of his time in office, and it’s easy to see how a systematic campaign to paint him as incapacitated could have backfired.

And yet, not all of the old rules have gone by the wayside. Even as President Trump behaves in unhinged ways, even as his speech undergoes a noticeable reduction in clarity and complexity, even as his own advisers confide in reporters that they worry about his stability, and even as the general public conversation about it has grown louder — there has not, until recently, been a serious effort from Democrats to question the president’s basic faculties. Whether this has been out of a fear of overreach, a sense of political propriety, or other factors is hard to say, though it’s difficult to imagine congressional Republicans holding their fire with a similarly erratic Democratic president.

In any case, it’s a reality that seems to be changing. Forsaking the so-called Goldwater rule that forbids diagnosing presidents from afar, Democratic lawmakers recently invited a Yale University psychiatrist to testify about Trump’s deterioration; she warned the group, which included a Republican senator, that the president is “going to unravel.” A Democratic congressmember introduced a gimmicky resolution to require future presidents to disclose the results of medical tests before an election.

But amid the nonstop chaos, it’s notable that it’s still Democratic backbenchers, not senior leaders, or even senators, who have sounded the mental-health alarm. (The highest-profile move in that direction has come from a Republican.)

If that reality changes, it will be yet another sign that we’re in uncharted waters.

The Media Mostly Played Nice

Peak media speculation about Reagan’s fitness came after his disastrous 1984 debate performance. The New York Times reported that the “age issue” dominated headlines in print publications and on national TV news in the aftermath. A Wall Street Journal headline that week went farther than most: “Reagan Debate Performance Invites Open Speculation on His Ability to Serve.”

But they cropped up again amid the Iran-contra scandal, when Reagan claimed to have forgotten key details about his administration’s selling of arms to Iran to fund Nicaraguan rebels.

In 1987, The New Republic ran the headline: “Is Reagan Senile?” But the takeaway was more about Reagan’s seemingly calculated forgetfulness than possible dementia. And the idea that Reagan was actually dangerously unfit never gained traction in the mainstream media. (Of course, there was also no internet at the time, making it far more difficult to stoke the kind of wild medical speculation that hurt Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign.)

If reporters had been fully forthcoming about their experiences with Reagan, the press could have been much worse. In her 2000 book Reporting Live, CBS’s Lesley Stahl recounted a startling interaction with Reagan in 1986 — she described him as “vacant” and “a doddering space cadet” — that left her questioning the president’s mental fitness. She came close to reporting the full incident, she told Mother Jones’s David Corn, but decided against it when the president quickly “recovered.” In later years, advisers and others would observe that while Reagan grew markedly less interested in the quotidian tasks of the presidency as the years went on, to the point of almost entirely disengaging, he still had the ability to turn on the telegenic charm he was famous for and appear perfectly lucid when needed.

The press often portrayed Reagan as doddering, but he usually came off in the end as benevolent or, in the case of a famous Saturday Night Live sketch, menacing — not incapacitated.

In 2018, questions of Trump’s mental fitness are far more out in the open than they ever were with Reagan, thanks to two factors: Trump’s clearly aberrant behavior and the public town square that is the internet, which feeds a constant speculation loop. There is certainly no shortage of national commentators proclaiming Trump unwell. For instance, CNN’s Brian Stelter opened an August show by asking if the president was mentally ill. In May, Joe Scarborough called the president “a man in decline” on MSNBC. During the campaign and after, armchair psychiatrists diagnosed the president with narcissistic personality disorder.

Legacy media outlets like the New York Times and Washington Post have, for the most part, been more cautious in their assessments — for now. Whether their standards will hold depends on whether the president’s behavior grows even more unhinged, which seems like a safe bet.

Reagan’s Staff Had Faith in the President

During his presidency and after, Reagan’s inner circle mostly testified to the president’s intelligence and ability to retain information. When Howard Baker became chief of staff in 1987, he recalled a decade later, “It did not take me a day to figure out that this man was sharp, well organized, fully capable, and the same person that I knew from previous years.”

But The New Yorker’s Jane Mayer wrote in 2011 that “by early 1987, several top White House advisers were so concerned about Reagan’s mental state that they actually talked among themselves about invoking the Twenty-fifth Amendment of the Constitution, which calls for the Vice-President to take over in the event of the President’s incapacity.” She recalled that “they told stories about how inattentive and inept the president was. He was lazy; he wasn’t interested in the job. They said he wouldn’t read the papers they gave him — even short position papers and documents. They said he wouldn’t come over to work — all he wanted to do was to watch movies and television at the residence.”

And in his biography of the president, journalist Lou Cannon wrote: “The sad, shared secret of the Reagan White House was that no one in the presidential entourage had confidence in the judgment or the capacities of the president.”

Here it is useful to examine the single biggest difference between the final years of Reagan’s presidency and the unprecedented situation we find ourselves in now. That is Reagan’s temperament, which was steady and reassuring even under duress — closer to President Obama’s cool demeanor than Trump’s impetuous-schoolchild routine. Even though Reagan could seem checked out to a degree that probably would have frightened the public, his aides did not alert reporters that they were alarmed by their boss’s mental state, in part because they did not fear that a true disaster would arise from his condition.

But Trump’s White House is leakier than a sieve, and while elected Republicans are fearful of crossing Trump in public, the president’s purported allies and confidants have no compunction about telling reporters what they really think of the president.

Whether Reagan was ever seriously impaired in office or not, his natural aplomb, both in public and private settings, gave him cover for his lapses. Trump, on the other hand, seems only to grow less tolerant, more impulsive, and more dangerous as he hurtles through his early 70s. His instability is right out in the open for everyone to see, and only his hardiest defenders — the Kellyanne Conways of the world — can consistently stick up for him without occasionally taking him to task.

And yet almost the entire Republican Party has decided to come to terms, in every important way, with their maniac-in-chief. In the end, it will be the actions of Trump’s allies, not their words, that determine whether or for how long their manifestly unfit leader will despoil the presidency. Don’t hold your breath.